The story in Acts 8 takes place on the side of the road in the wilderness, and at a crossroads, an intersection. I am not referring to the wilderness of the roads from Jerusalem to Gaza – there was no single road in the Roman era that transversed the fifty miles from Jerusalem to Gaza. One would have to travel a series of spider-web zig-zagging roads from Jerusalem south to Hebron, west to the Ephrathah Valley crossroads, south to Beersheba and northwest to Gaza on the coast, if one wanted a chariot-capable road. (Hebrew Bible students should be checking their atlases and reminding themselves for whom the Ephrathah Valley is named in preparation for next week’s examination.)

The other wilderness in which this story from Acts takes place is the wilderness of biblical interpretation. This wilderness is also marked by a crossroad. At the intersection of race and ethnicity, the Greek gentile Philip crosses paths with the black Jewish bureaucrat whom I’ll name shortly.

In this same wilderness, Jewish Scripture intersects Christian Scripture and Jesus is right in the middle, literally at the crossroads. For Philip, the Gentile, the whole bible is apparently all about Jesus. But to be fair, he was probably taught this system of exegesis by Jews, who although and perhaps because, they recognized Yeshua ben Miryam L’Natzeret, Jesus of Nazareth, Mary’s Baby, as the Messiah of whom their prophets prophesied, still identified themselves as Jews, as Israel.

What can we learn from this wilderness encounter at this particular crossroad? Should you who have been laboring for the better part of a year to supplement your Christian interpretive lenses with ancient Near Eastern and Israelite contextual lenses grind those new spectacles under foot and return to wearing your former prescription? Does the story in Acts mean that the Hebrew Scriptures are really the Old Testament and are in fact all about Jesus who is in fact lurking under every bush in the bible? Is this going to be on the final?

What if I were forced to answer the question I keep asking my students: What is a faithful Christian reading of Isaiah 53 that preserves its ancestral contextual integrity? What if I were in that chariot? What would I say? And perhaps most importantly, would the Kandake’s servant still be baptized?

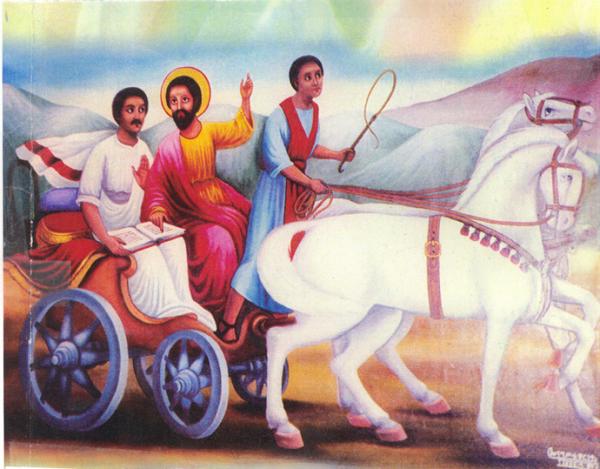

Let me begin (again) by retelling the story and filling in a few details. There is a biblical tradition that extends to modern Ethiopia of naming royal servants after their monarchs. Some of the names of biblical servants and eunuchs that are attested in Amharic, the contemporary Semitic language of Ethiopia include: Avimelek – my father is king, (this name is also found in the bible for men who are not royal – or other – eunuchs or servants.) Abdimelek – servant of the king and Melech – literally “king” but used as an indication of servitude. These two names belonged to Ethiopian eunuchs who served in the Roman Era in Rome.

Borrowing from this tradition, I will call the official Abdimalkah, “servant of the Queen.” Because he has a name and, the fact that it has been lost to us does not mean that he should be stripped of his dignity along with whatever else he may have had to surrender for his career. We’ll come back to his sacrifice.

I have named him Abdimalkah, because he was in fact, a servant of a queen. The Kandakes were the Queens and Queen Mothers of Meroe on the Nile – the Anchor Bible Dictionary persists in calling it a “kingdom” in spite of the fact that women and ruled there individually and only occasionally had male co-regents. The Kandakes were well-regarded warriors; some taking on the mighty Roman Empire and, the Kandakes were also priestesses of Isis. A second century BCE historian said that the Kandakes were the only real rulers in what I translate as “a queendom.”

While the Kandake in Acts is not named, she is very likely Kandake Amanitore, the co-regent of Meroe, called Kush in the Hebrew Scriptures who reigned from about 1 to 20 or perhaps as long as 50 CE. Kush was later called Nubia and finally, Ethiopia. It corresponds with parts of contemporary Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt.

Kandake Amanitore is the most likely referent because her monuments that exist to this day would have been well known during the first century. Her successor, Amantitere, is also a possibility.

The writer of Acts may well have expected readers to know all of these things. There is another relevant tradition, that of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, that when Solomon and I quote 2 Kings – “gave the Queen of Sheba her every desire” she returned home pregnant and the two monarchies maintained friendly diplomatic relations across time, exchanging gifts including the scriptures of Israel after their production.

This tradition maintains that Abdimalkah as I call him, was reading Kandake Amanitore’s copy of Isaiah on that wilderness road when he arrived at that crucial intersection. There is some support for this in the text; Abdimalkah has been to worship in Jerusalem. He is a Jew. Israelite religion would have been introduced to the people in the broader Ethiopian cultural context by the Sheba-Solomon connection.

So let us use what my ancestors called sanctified imagination and see what would happen if I were Phillipa and I joined Abdimalkah in his chariot. I would say, “Abdimalkah these words:

And he, because he has been ill–treated,

does not open his mouth;

like a sheep he was led to the slaughter,

and as a lamb is silent before the one shearing it,

so he does not open his mouth.

In his humiliation his judgment was taken away.

Who will describe his generation?

Because his life is being taken from the earth…

These words are from the Greek Scroll of the prophet Isaiah and were written more than four hundred years ago. I know that they are a bit different from the Hebrew Scroll of this same prophet; that line about this man’s life being taken from the earth isn’t in the Hebrew one.

You ask of whom does the holy prophet speak? I tell you, it is Jesus of Nazareth who was crucified, and more than that, who rose from the dead in our very days. I knew him; I sat at his feet and learned the scriptures of Israel from with and through him. I heard him teach that we should touch the untouchable, love the unlovable and forgive the unforgivable because that is how God loves us. And more, this virgin-born Jesus, who was and is God-in-Human-Flesh, Immanuel in the Hebrew tongue which I know is related to your own language, has power that no one has seen since the days of the prophets of old. When I hear these texts, I hear Jesus because of my experience with Jesus.

But they have other meanings as well. The ancestors of the followers of Jesus from Judea believed that these words spoke of people in Judah in days gone by. The holy words spoke to them of those who suffer as they did when the Babylonians destroyed their nation. It spoke of the suffering of the innocent with the guilty and perhaps of the suffering of the innocent on behalf of the guilty. For many believe that the sins of their ancestors brought the destruction of the nation and even the Temple in which God dwelled on earth. But they were not all guilty. Yet they all suffered. In ancient days, people believed that to be cut off from the land of the living in this text was a description of Israel in exile and, the lengthening of days refers to the restoration of the monarchy. This caused no end of confusion when Jesus was teaching among us; some believed that he would launch an armed revolt against the Romans.

I have learned from studying the scriptures of Israel with the Judeans that even when sacred scripture was understood in a completely different way in another time, it speaks to those of us who hear and read it today in our time. And some say, that it will continue to speak to generations, yet unborn across the ages.

Abdimalkah, I believe that these verses speak of Jesus of Nazareth who waded in the waters of the Virgin’s womb, walked the way of suffering, and woke from the grasp of death in the deep darkness of the morning.

And, seminary community, I believe that interpreting the scriptures of Israel in their own context does not diminish the proclamation of the Gospel. It is in fact a greatly impoverished gospel that can only stand on texts whose sure foundation has been eradicated.

And I believe, that when God decided to give birth to the African Church, a Church that survives into modernity without schism or reformation, and God appointed Philip as its midwife, and that Abdimalkah the eunuch becomes God’s firstborn in this new and continuing community.

In order to work for most monarchs in the ancient Near East and North Africa, men had to be surgically neutered. The monarchs did not want top-level employees trying to pass on power to their children and establishing dynasties of their own, or forming adulterous liaisons and undermining the government. Ironically, most eunuch formed intimate partnerships with other eunuchs or intact males, not royal women.

What then are we to make of these things as we prepare to leave this place for all time or for some time? There are several ways in which we can consider eunuchs.

First, we can consider them to be anachronisms; that is, they are relics of an ancient time and antiquated social system and do not have parallels in our modern-techno-web-based society. For who among us would voluntarily sacrifice his plumbing for a job? There is at least one contemporary parallel, in a nuclear reactor in a small town, nearly destroyed by unemployment some years ago, some women were hired at an unimaginable cost. Those who were of child-bearing age had to agree to be sterilized, so that there would be no possibility of lawsuits over babies with birth defects. That employment contract was eventually overturned.

The last way we can understand eunuchs is as social and sexual outsiders. There are many who view lesbians, gay men, bisexuals and those in the process of having their gender surgically altered as outsiders from the fold of God and society at large. Those who are born with an indeterminate gender or who have been injured – burn patients often loose all of their extremities including their genitalia – quadriplegics, paraplegics and infertile women and couples can also feel like sexual and social outsiders.

All of these folk for one reason or another do not fit in the dominant image of the American dream in which every woman was born to be a mother and every man was born to be a father in a hetero-patriarchal marriage that produces 2.4 children. There are many who consider anyone who doesn’t want to, or is not able to have a ‘traditional’ family as outsiders to the American dream and ‘traditional family values’ advocated by churches in the name of God.

Eunuchs can then be seen as those who do not fit into our neatly constructed gender paradigms as neatly as we might wish. If we understand eunuchs to be social and sexual outsiders whether born or made, then God chose to birth the faithful African Church though a queer person’s body.

This Gospel is that God’s concern for the woman-born was manifested in God, Godself, becoming woman-born, for the redemption and liberation of all the woman-born: gay, straight, crooked and confused, from fear and from death itself. Yeshua the Messiah, the Son of Woman, came to seek out and save the lost and to give his life as a ransom for many.

13 May 2009

The Rev. Wil Gafney, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Hebrew and Hebrew Bible

The Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia

Article Comments