Let us pray: In the name of the One who waded in the waters of Miryam’s womb, walked the way of suffering as one of the woman-born, and woke from the grasp of death in the deep darkness of the morning. Amen.

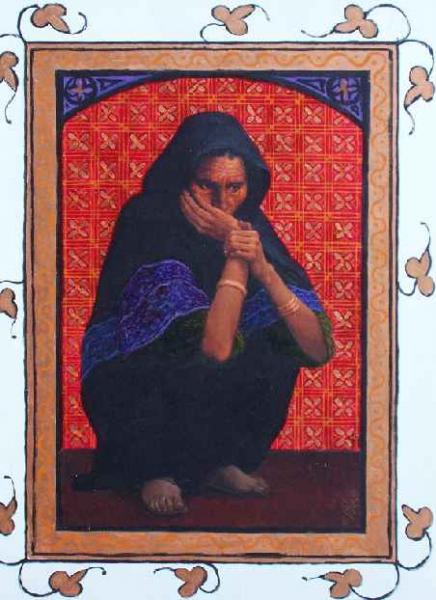

Sarah’s daughter was bleeding from her vagina, again, still. It wasn’t the not-so-secret monthly blood whose scent was part of the cacophony of smells which perfused the Iron Age and passed largely without comment from anyone else. This was something else entirely. This was a flow that never quite stopped. It dwindled from time to time, giving birth to aborted hope that this time it had stopped for good. A day or two of respite, and then the bleeding started again. There were some years that she had gone for months without bleeding at all. And just a few months – she could count them on one hand – that she bled like other women. She had bled this way since her first bleeding. It was nothing like what her mother and aunts told her to expect. Her sisters didn’t bleed like this. She drank the teas the midwife gave her, tied the knots in the cord around her body as prescribed by the healing prophets (like those in Ezekiel 13), nothing helped. She never felt clean. There were stains on all her clothes, her chair, her bed. She was tired, tired of bleeding and just tired.

She had moved to a town where no one knew – or admitted that they knew – her story. She couldn’t stay at home any more; all of her sisters were married and having children. She loved her sisters and their children and yet every time she saw one of them blossoming with yet another pregnancy or putting a baby to her breast she felt an ache in her empty, broken, bleeding womb. The other mothers in town wouldn’t consider her for their sons. She could have married an older, widowed man to help him with his children, but that wasn’t the life she wanted for herself. And she made a decent life for herself, as a midwife, a healer, hoping to learn something that she could use to heal herself. She also became a midwife because she hoped no one would think twice if they saw blood on her skirts. All of the money she earned, all of the goods and services she received, she sold or bartered away in hopes of healing herself. She spent all of her income on every healer and physician in her town, within walking distance and sometimes beyond. She was Sarah’s daughter and she decided to do whatever it took to heal herself, save herself, to live.

Her vaginal hemorrhage didn’t affect her day-to-day life as much as people might have imagined when the flow wasn’t too heavy. After all, being ritually not-yet-ready for worship – a better translation than “unclean” in terms of illness or naturally occurring bodily cycles – was quite common and in most cases remedied by bathing and an inexpensive offering. Some cases also required physical inspection by a priest or for women – I believe – a woman who was both the daughter of and the wife of (another) priest with the pronouncement of restoration being made by the priest. But her vaginal bleeding would have to stop first, long enough for her to qualify for and pass inspection. And in the past twelve years it hadn’t and as a result she couldn’t go to Jerusalem and worship in the temple, and she wanted to go. She had been there as a child, but she wanted to go as an adult and take her own offerings and say her prayers facing the place where the living God resided, bathed in clouds of incense. It wasn’t required for women, but so many women went that there were mikvahs – baths – dedicated for them, there was a plaza named in their honor and, special gates and balconies for women who didn’t want to mix with men.

Even though she poured herself into the healing arts and her life-giving work, rejoicing at each new life born into her hands, Sarah’s daughter longed to be free of her terrible illness, the weakness, the pain, the constant washing and cleaning and to have some new things, new clothes, unstained. Her affliction also affected her sense of herself, her sense of her own value and beauty and worth. She was distant from her own family and had no family in this town. She had no one with whom to share Shabbat meals, she lit the candles by herself. Sometimes families she helped invited her for celebrations but she was always afraid her body would betray her, like that one time she thought she had enough padding and then it broke through in front of everyone. She had moved again after that. She was keenly aware that her body didn’t work like other women. She felt broken. And she knew she could die from this.

But Sarah’s daughter refused to be destroyed by her pain or paralyzed by fear. She didn’t know why her body was the way it was, but she knew it didn’t have to be. She knew it could be, should be, would be different. And she would do whatever it took to save herself, be healed, be made whole, be restored, to live – the verb means all of those things. She had heard that there was a miracle-working rebbe, Yeshua ben Miryam, (Jesus, Mary’s child) based in Capernaum who regularly crossed the Sea of Galilee. And today he was here. She was going to see him.

As she hurried after the crowd, she thought about what she was going to say. She followed the sound of the commotion and saw more people gathered than lived in her town. All of them pushing towards a group in the middle, and one of them… Yes him. He’s the one. She pushed. Not caring if some stepped out of her path because they saw or smelled the blood that was flowing even harder. She had to reach him, had to get his attention…

But he was walking with Ya’ir (who the Greeks called Jairus). Ya’ir’s daughter – what was her name? was it Me’irah? Named for “light” like her father? I think so – Me’irah had died. A child whose whole life was the length of her disease, twelve years. And now she was dead. Sarah’s daughter said to herself, I won’t bother the Rabbi. He must go to comfort Me’irah’s mother.

She was all alone as she watched her daughter die, she was all alone as she planned and began the funeral of her child. She was like so many mothers left alone to do the difficult work of holding her remaining family together through the most trying of times. Her husband had not abandoned them, but he had left them. He missed the moment when the light left his baby girl’s eyes as she passed from life to death. He left her on her deathbed and her Mama in her deathwatch in the hope that he could persuade Rebbe Yeshua, Rabbi Jesus, to come and lay his hands on her. But she died in his absence and they started her funeral without him…

Yet Sarah’s daughter couldn’t walk away; she couldn’t take her eyes off of him and found herself within a hand’s breadth. Falling to her knees, reaching out, not knowing what she would do until she did it; (according to the other two gospels) she touched his tzit-tzit, the knotted fringe on the corners of his clothing – the sign of an observant Jew. She believed that this time she would be healed. She had believed before and been disappointed, but that didn’t matter. Sarah’s daughter had resilient, indefatigable, inexhaustible, inextinguishable faith. She said, “If I but touch his clothes, I shall be saved.”

More than healed, saved, saved from the death that was surely coming closer. Twelve years of pain, disappointment, sorrow and struggle did not diminish her faith; it was a living thing, carried inside of her, extended through her hand to One who was so worthy of her faith that he didn’t have to see her, speak to her or even touch her to save her, heal her, make her whole, grant her life and transform her.

And it was so. She drew the healing power from his body. She did it. The text is full of her verbs: She endured, she spent, she was no better, she grew worse, she heard, she came up, she touched, she said, she felt, she was saved/healed/restored and then she told him everything. Everything. All her pain, all her grief, all her hope, all her faith. All. She is the active agent in her healing eleven times, and once passive – her hemorrhage stopped.

And Ya’ir, Jairus, is waiting and watching. He left his child on her deathbed to find Rabbi Yeshua, Rabbi Jesus. He didn’t know if she would be living or dead when he got back; but he knew that if Yeshua, Jesus, just laid his hands on her, she would be alright. Ya’ir started his journey in faith. He said, “My little daughter is at the point of death. Come and lay your hands on her, so that she may be saved, and live.” (There’s that verb again.) And Ya’ir ended his journey in faith. When he found Jesus, he found resurrection and life at the same time Sarah’s daughter found restoration and life.

One of the great ironies of the aftermath of this text is that the church of Jesus Christ and nominally Christian societies like ours have become so scandalized by women and our bodies that we dare not name our parts or the problems with our parts in polite company according to some folk. It is ironic, because silencing women and censuring our bodies denies the Gospel story itself: That God became flesh and blood in the body of a woman, was nourished by her blood in her body passed through an umbilical cord attached to a placenta, rooted in the wall of her uterus, and one day pulsed into this world through her cervix and vagina. Just like the rest of us – give or take the occasional caesarian.

This is the scandal of the Gospel, the Incarnation of a woman-born God. At the heart of Incarnation theology is the notion that the human body – and women are fully human – is neither accidental nor unworthy of the habitation of God. The scandal of the Incarnation is the scandal of the human body in all of its forms, genders, expressions, orientations, nationalities, ethnicities, abilities, limitations, communicable diseases, poverties. And this is what God became, for Sarah’s daughter and Ya’ir and his daughter and her mother and you and me, for the whole world, for all of groaning creation. To paraphrase Brother (Cornell) West: Jesus was born too close to urine, excrement and sex for the comfort of many. God became human to touch and be touched by the broken, bleeding, dead and dying and to be broken, bleed and die. And in so doing transformed that brokenness into a sacrament, body and blood, bread and wine, the shadow of death, grave-robbing resurrection.

This Gospel is that God’s concern for the woman-born was manifested in God, Godself, becoming woman-born, for the redemption and liberation of all the woman-born from fear and from death itself. Yeshua the Messiah, the Son of Woman, came to seek out and save the lost and to give his life as a ransom for many. Amen.

Leave a Comment