In the name of the faithful God who has redeemed us, Amen.

In the name of the faithful God who has redeemed us, Amen.

The days are surely coming, says the Holy One, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah. Jeremiah 31:31

It is almost impossible for Christians to not read the new covenant in Jeremiah 31 as the new relationship between God and humanity inaugurated by Jesus or as the New Testament. We just can’t help ourselves. The disciples and early church read the Hebrew Bible in light of and looking for Jesus. Jesus himself is recorded as speaking tantalizingly about the ancient scriptures referring to him but he didn’t say how. Did he mean as himself, Jesus ben Mary; did he mean as the God who is ever present in the text?

There is a real temptation to read prophetic texts as predictive and only predictive. But that misses the contemporary ministry prophets offered in their own time: speaking to the current circumstances in which folk found themselves. When we start by reading ourselves into the text we miss or even erase the faithfulness of God to her people across time. We need the witness and promise of that faithfulness. We need to know that God will be faithful because God has been faithful.

God makes this promise of a new covenant to Israel and Judah at a specific moment in history. The period in which Jeremiah 31:31-34 is set might well be called a post-apocalyptic horror-scape. I’m not certain hearers of this text always understand what all is implied by the Assyrian and Babylonian conquests, deportations, and exile of Israel Judah because we in the US do not have the experience of sustained warfare on our shores. To understand this text, envision the news accounts of the war in Syria: rubble and destruction everywhere, smoking ruins everywhere else except those things that are already on fire, brutal executions, bodies in the streets, even the targeting of children to terrorize the population, starving, desperate people.

Jeremiah is addressing the decimation of Israel by the Assyrians a century earlier followed by the Babylonian invasion and its aftermath in his own time. His message is that Israel will be made whole. God had not forgotten, even though their near annihilation by the Assyrians was unresolved, even though the Babylonians had now savaged the remnant that was left.

The nation was broken. Jeremiah, like many in his time, blamed all of Israel’s misfortunes on them; it was all their fault because they were sinners. Unfortunately that theology didn’t die with him. Yet, Jeremiah did get something right. He knew that God was faithful. He knew that God’s desire for her people was wholeness. He also came to know that nothing Israel did justified the brutality they experienced. That theology inevitably fails, usually when the person blaming others suffers some misfortune they know they did not bring upon themselves.

And Jeremiah knew the brokenness of the world wouldn’t be made whole overnight. In the verses before the ones we read, Jeremiah describes how it will be: The land that was ravaged will be replanted, human and non-human life will thrive. Seasons of planting and harvesting, and of construction and reconstruction will replace the seasons of terror and devastation Israel had experienced.

It is in this context that God says: I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah. Throughout the Hebrew Scriptures God’s covenant with Israel is torah, which means teaching more than it does law. This constitution, if you will, was not a document signed by founding fathers or first mothers; it was a covenant with God. Now God says: I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah. (Jer 31:31)

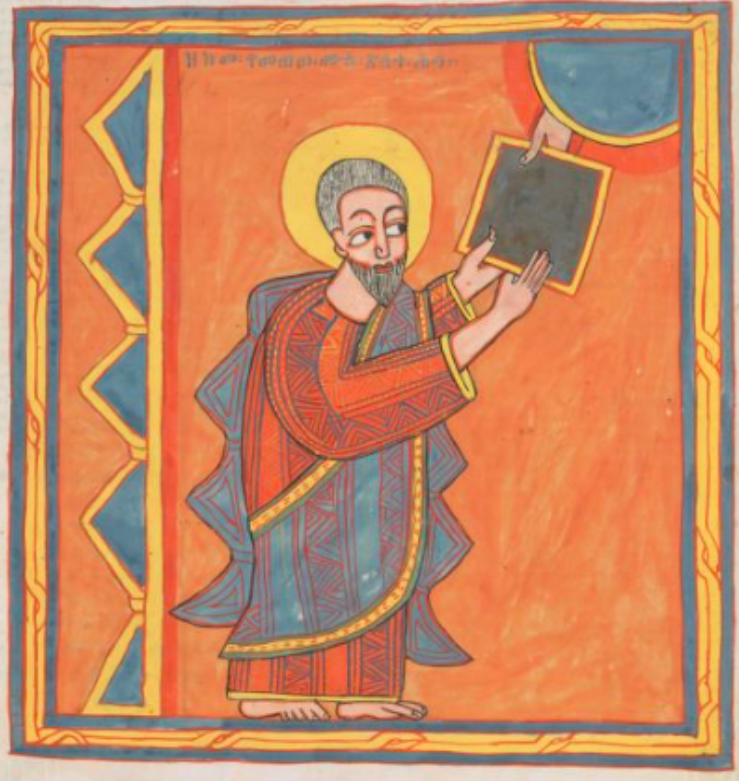

Some may hear “another” covenant in the “new” covenant but God isn’t throwing out the Torah, the teaching, the laws that distinguished Israel to some degree from other nations. Rather God is doubling down on it: I will put my torah, my teaching, my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts. I will be their God, and they shall be my people. (Jer 31:33) The tablets on which God had written the prologue to the first covenant were gone. Their shattered pieces were kept in the Ark of the Covenant and no one had seen that since the Babylonians assaulted the temple with axes and with fire.

To these broken and devastated people who had lost all of their institutions of statehood and peoplehood–monarchy and worship, liturgy, and sanctuary–Jeremiah offers a word of hope. The nation, which is also the religious community of the faithful, will be reconstituted. They will be rebuilt, reborn. They are getting a second chance. Jeremiah’s prophecy was good news to his people living in the last tribal enclave of Israel after the Assyrians demolished every tribe outside of Judah, good news to those deported by them, and good news to those who survived the Babylonian onslaught. And it is good news to us, even though we are not in the same circumstances.

Because scripture is living, it is pluripotent and can do more than one thing. It testifies to God’s faithfulness in the past, and promises the surety of that continued faithfulness in our time and beyond. Jeremiah describes a world in which people who saw their nation ripped apart, their fellow citizens deported, their families torn asunder, their economy ruined, and another nation ruling them through a puppet they installed. I know Jeremiah has something to say to us in our time: God will be faithful because God has been faithful.

It is these values, the trustworthiness and power of God to redeem and restore that the evangelists saw as contiguous with the life and teaching of Jesus. In short, Jeremiah does not so much predict Jesus, (though he and his writings may); rather the text renders a portrait of the God whom Jesus incarnates. This God embodied in Jesus stands against empires and their domination. The Assyrian Empire fell. The Babylonian Empire that replaced it fell. The Persian Empire that replaced it fell. The empire of Alexander the Great that replaced it fell. The Roman Empire that succeeded it fell. The Holy Roman Empire fell. The Byzantine Empire fell. The Ottoman Empire fell. The sun set on the British Empire. Imperial power is based on subjugation, the antithesis of the liberty God offers through Jesus. Empires fall and we as Americans need to take heed.

The backs of tyrants and their empires will be broken. But the people ground into the dirt by them, and even those who have served them are the people whom Jesus draws to himself, even as the empire of his age put him to death: Now is the judgment of this world; now the ruler of this world will be driven out. And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself. (John 12:31-32)

The ancient Israelites and Judeans partnered with God in their restoration. They lived into the covenant that was the teaching of God, passing it down to every generation that followed. We are watching things change around us, with the echoes of their testimony in scripture in our ears. And we can see the workings of empires no longer limited to nations states in the way in which peoples are treated, subjugated, used for cheap labor, and discarded. Now as then, God calls us back to the commandments, the teachings, the torah, the law of God, not just in our ears or before our eyes, but engraved upon the tablets of our hearts.

While God rights the world, restoring all that is broken and Jesus draws all–no exceptions, all–to him, we are called to live that covenant, its commandments, teachings, and laws. For God will not right the world by a sweep of a divine hand; we will feed the poor, house and clothe the homeless, work for peace between people and nations, leaving only the impossible up to God. The possible, the difficult, the undesirable; that is all our work.

In this season of Lent we start our services with that covenant to remind ourselves and recommit ourselves to this covenant: We will have no other gods but God. We will not make anything an idol. We will not dishonor the Name of God. We will honor the sanctity of the Sabbath. We will honor our parents. We will not break faith with our beloveds and we will honor the sacrament of marriage. We will not steal. We will not lie. We will not covet our neighbor’s possessions or position. We will love our neighbors as ourselves. (Ex 20:3-17; Lev 19:18) We affirmed this covenant when we said, “Amen, God have mercy.” We were saying, “God have mercy on us if we fail to uphold this covenant.” We say that, because we know that we will fail and we trust in God to have mercy.

We trust in God’s love, faithfulness, and mercy, and in her promise. I will be their God, and they shall be my people. Amen.

David Jones

March 19, 2018 9:47 amI have been trying to get my congregation to read the Hebrew scriptures in their original context. I am going to try to arrange for a rabbi to interpret those texts that the church superimposes Jesus on so we can see what they meant to the folk who first heard them and read them.

Wil

March 19, 2018 11:16 amBless you in this work. Consider using the Jewish Publication Society Study Bible. It has excellent scholarly Jewish commentary as does the Jewish Annotated New Testament.

Tahita Fulkerson

March 21, 2018 9:54 amWil, I especially love this and have shared it. My friends love getting my e-mail when it shares your work. Thank you for being always thoughtful.

Wil

March 21, 2018 11:34 amThank you! (Stay tuned for today’s sermon from our Episcopal Eucharist!)