Today’s readings come from the Women’s Lectionary Year W Proper 9: 1 Samuel 2:12–17, 22–25; Psalm 49:1–2, 5–9, 16–17; 1 Timothy 6:6–16; Luke 16:10–13

The sermon may be viewed at All Saints Kauai. The message begins at 26 minutes.

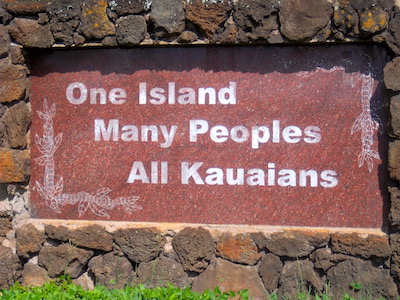

It’s good to be back on my island home. Much mahalo to Kahu Kawika for the warm aloha welcome and invitation back to this cherished pulpit. I am also delighted to share with you A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church, a new way of translating, reading, hearing and preaching scripture centering women’s stories, published by our Episcopal Church publishing house. Let us pray.

It’s good to be back on my island home. Much mahalo to Kahu Kawika for the warm aloha welcome and invitation back to this cherished pulpit. I am also delighted to share with you A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church, a new way of translating, reading, hearing and preaching scripture centering women’s stories, published by our Episcopal Church publishing house. Let us pray.

May the spoken word of God draw you deeper into the written word of God and kindle in you a passionate love for the Incarnate living word of God. Amen.

What are you hungry for? Money. Sex. Power. Oh my! Money, sex and power are the source of a whole lot of trouble in and out of the church, even without the visceral reminder occasioned by the news of Bill Cosby’s release – after I had finished writing this sermon. Yet money, sex and power are not inherently evil or sinful. They simply require good kuleana, stewardship and accountability and, the need to move beyond the polite politics of respectability and the various closets of shame to frank public and private conversation. Our reading gives us an opportunity to do just that, even if we squirm in our seats a bit. In just a few Sundays listening to Kahu Kawika, I know he loves a good movie quotation so I say, “Buckle up buttercups” we’re going to talk about money, sex and, power and, why we need to talk about them, especially in Church.

It’s hard to talk about money, wealth, income. It’s embarrassing. It’s private. It can be a mark of shame. It’s a signifier of class, privilege, inequity, poverty. Access to money and credit have been used as suggestive of industriousness, skill, even character or the lack thereof. It accumulates and depletes through careful stewardship, dumb luck and sometimes, in spite of our best intentional efforts.

In the ancient world bread was the “staff of life.” Some of you who were around in the seventies will remember that before we called money cheese, cheddar and gouda or stacks, we called it bread. We need money to survive in this world. But money is not easily or abundantly available to all. It’s very necessity makes it easy to covet and idolize and makes those who lack it vulnerable to pressure do what they would never ever do – out of greed and sometimes out of desperation. Money is seductive. But money and those who have wealth are not bad – or in biblical terms, evil.

Our discomfort with money means that some income-based inequities persist in silence, even in the Church. As long as it’s taboo to discuss salaries openly, some folk will find themselves underpaid in comparison with their colleagues, most often resulting in black and brown folk and women of all races being paid less for the same job. Poverty and wealth inequity disproportionately affect women and children in our world and in the world of the scriptures. Persons with power and authority always had more and always wanted more. And for some, “more” would never be enough.

The economy of ancient Israel was so different from our own that direct comparisons are not always possible. Their kahus did not receive a salary and heath care benefits; they lived off of the donations of the people, preferably material. There was actually a surcharge for tithing cash because the Levites would have to convert it into the goods they needed. We can’t imitate that system, not even if every member diverted ten percent of their solar energy to the church or brought in ten percent of their Costco haul. Our churches and clergy have completely different needs in the digital age. Cash, currency, paper, plastic or digital is infinitely more useful than one out of every ten sheep or goats.

In in our first lesson there are women who make their way to Shiloh to make their offerings. And, there were women who ministered at the sacred tent and had a formal role stationed in the military sense at the tabernacle. There were also the wives of the men who are at the center of the story, perhaps there were daughters as well. As is so often the case, men who commit acts of corruption and abuse have families who suffer from their choices. If we were to read forward two chapters, we’d find one of these men had a heavily pregnant wife who would be left with a baby and the legacy of his mess. And isn’t that always the way? Poor choices seem to rebound to everyone else but the perpetrator sometimes. And when they do pay the price, their family pays along with them.

The material needs of the priests and their wives, daughters and sons come from the offerings the people bring to God. There is a specific formula of what goes to God and when. The first and the best go to God. That is a principle that many have adopted when translating the world of the scriptures into our world, that we give back to God before we take anything for ourselves, that we support the work of God with our best gifts. In the world of the text, that looks like a Sunday supper potluck, pupu and aloha hour, Texas barbecue or luau (except for the non-kosher pig and communally sacrificing the critters we’re going to barbecue after service today). People brought their animals and their gifts of fruit and oil and wine and grain and bread. There was a liturgy of slaughter and choice portions of meat and other offerings went to God and the house of God and, a portion of that went to the priests. The rest went back to the folks who brought the offerings; those portions were shared among the people there so that a poor person who brought only a bird might dine on lamb.

Against this background Eli, the priest at Shiloh, one of the major religious centers of ancient Israel, had sons in the priesthood who were corrupt. Imagine the ushers passing the sacred calabash and sticking their hand in it and putting some of the money directly in their pocket. Not waiting until the offering has been blessed and deposited and then running a sophisticated embezzlement scheme, but just pocketing it openly, snatching it out of your hand, and yelling at you, “I want my cut now!” And then telling female congregants, “Meet me out back, I want something else too.” It is a crass and distasteful story and, it is part of our scriptural heritage because these things occur in our world in just as they do in the scriptures.

There is much more than “money” or its livestock equivalent at stake here. Money and power are intertwined. And, with the abuse of power band financial inequity often comes the harassment and abuse of women. Eli’s sons violated the standards of the community and committed what we now call clergy sex abuse abuse against women in their congregation. We have all seen these kinds of stories in the news, stories of the abuse of women and girls and boys and men. The names of other churches might occur more often in the news but our church has its own sad stories. It was of the church that Lord Acton infamously said, “power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” We know that men using power and authority to force women into what they would never have agreed to is not limited to religious spaces.

I like this text because even with the patriarchy, hierarchy and biases in the text, God’s concern for the most vulnerable is always present. What the text is saying perhaps surprisingly in the Iron Age, is there was no “pass” for men of privilege and status to abuse women. The women in the text didn’t have to keep telling their story for twenty years until somebody took them seriously. The women in the text didn’t have police officers who refused to take their statements or to open investigations because the men they accused were important, father figures in the community. In the theology of the text, these transgressions against God and God’s people, against the congregation and the daughters of the congregation were unforgivable and they would not be allowed to continue. God would take the lives of the perpetrators. This matters in a world in which laws and legal systems fail, sometimes by design. There was no amount of fancy or high priced lawyering that would get those God had pronounced guilty off for their crimes.

Another lesson to take from this story is that secrecy about misconduct enables misconduct, whether fiscal or physical. That’s why it’s important that we teach and preach these stories, that the church be a safe place from violence and corruption and a safe harbor for those who have been preyed upon. And, we preach these stories because they keep happening and folk need to know that they are not alone and that God sees, hears and responds even when we can’t see how. We as Church must be worthy of the trust of those who have been wronged in and by the Church and its members and leaders and those who have been wronged outside as well. The Episcopal Church is just beginning to reckon with its participation in and profiteering from slavery and has yet to wrestle with its own history of residential schools like the ones in Canada where we have recently learned of mass graves of indigenous children; where the mission was often to strip the Indian out of native children, severing the roots of their culture along with the roots of their hair even punishing them for speaking their native languages. Hawaiians know something about that. Here in Hawaii the Church has done more to address its problematic history and legacy. Hula e mele live on because of and in spite of the Church.

Reading these texts together I use what we call in the black preaching tradition the sanctified imagination to conjure a conversation. I imagine what those women might have said or or prayed in response to their circumstances. Psalm 49 reads as though someone who was abused by one of those men asked, “Why is it that rich men can do anything they want to anybody?” And a wise kupuna speaking to rich and poor alike, the children of earth descended from Eve says, “Their wealth will not protect them; it cannot redeem them. They cannot take it to the grave. They will not live forever and the Pit, the judgement of God is waiting for them.” The promise of God in this text is that God’s justice is inescapable, as inescapable as God’s mercy.

Reading all of these texts together, I also imagine the person who wrote a letter to Timothy in Paul’s name reading the psalm and concluding, “We brought nothing into this world and can take nothing out.” The epistle is a philosophical approach to wealth and greed and the author could just as easily be reflecting on the story of Eli’s sons: The love of money is the root of all evil. Their greed led them to covetousness, theft, extortion, sexual violence and blasphemy. It wasn’t the money. It was the love of money. It wasn’t the power, it was the abuse of power.

Now some of you are probably having a sigh of relief since I’m talking about corruption among the clergy and not among the people. But the truth is many of us operate in systems where we have power and authority over someone else and the temptation to be corrupt, greedy, selfish or abusive is there for all of us. Ultimately these stories are about more than a particular salacious religious scandal. They are about the deep hungers and cravings we all have and the futility of trying to fill those voids with anything but God’s love. For some, the appetites for money, sex and power can never be satisfied because those things are not what they, we, are really hungry for. That’s what Timothy’s epistolary pen pal is addressing with, “take hold of the eternal life,” be hungry for that. Covet that. Scheme for that. There is a God-shaped space in each of us that we too often try to fill up with things that will pass away, things that will not satisfy, things that will hurt us and those around us.

Finally in this sanctified imaginary conversation between these writers and those they give voice to across time, Jesus says, “The woman or man who is faithful with little is faithful also with much; and the woman or man is dishonest in a very little is dishonest also in much.” Corruption doesn’t start with the scandal on the 6 o’clock news. If we are faithful in the small things no one knows about, we will be faithful when the cameras roll. And if we are faithful with whatever resources and relationships we have now, we will be faithful if and when we are blessed with the fruit of our stewardship and the gifts and graces of God.

As Church we have to talk about our secrets, the harm in the world and the harm in the Church, what others may not deem polite. On da aina you know that all kinds of nasty stuff grows in hidden and closed off spaces. Our ohana in recovery remind us that we are as sick as our secrets. Jesus preached so much about money and power and those who had little to none publicly, to model for us our kuleana our, responsibility for those in our midst and those around us in our shared world as na keiki a ke Akua, children of God. Amen.

Clare

July 30, 2021 12:47 amHello, I can’t find a way to message you directly so have resorted to a public comment. I discovered your work about a year ago and it has been incredibly nourishing and important for me. Thank you. As a white woman trying to decolonise my theology, employed to speak into a predominantly white middle class church, your insights, grace and passion are so helpful. I appreciate your academic rigour that is also grounded in pastoral concern and engagement with real lives, real issues, real people. I regularly check in with your blog when I am preparing a sermon, to ensure I consider a womanist perspective alongside other material, and not infrequently I end up quoting you somewhere when I speak. Thank you for your ministry, especially your ministry to those of us who are charged with interpreting the bible for our communities. Clare