Let us pray: Holy One of Old, open our eyes that we may see. Amen.

The author of the book of Samuel wants you to know that good things come in small, or better, seemingly insignificant packages. David’s own father – Happy Father’s Day! – overlooked him because he was the baby. Samuel wasn’t much better, focusing his attention on the tall, dark and handsome brother. But God says, “I do not see the way that humans do: you all look at a person’s face and body; I look at a person’s heart.”

Samuel and God were having this conversation because God had decided to replace Saul as king. Saul, the second king in Israel after Avimelek in the book of Judges, has turned out to be something of a disappointment. And God breaks up with him. Saul is devastated and never recovers, and I really feel for him. Samuel seems to take it equally hard. But the bible and God move on to David – ah new love!

God has had God’s eye on David’s family and decided on David as the next King of Israel. What was it God saw in the young David? I’d like to think it was promise and possibility. I’d hate to think that God saw all of the things that David would do and chose him anyway, not caring. I’d rather think that God saw that David had it in him to be a great man, to inspire people, to lead people, to love passionately, to pray faithfully, yes, to sin, but then to repent sincerely. So God sent Samuel to Jesse, to anoint one of his sons – as yet unidentified. God tells Samuel to invite Jesse and leaves the rest of the details up to him. And that’s where things get interesting.

I’m calling this sermon “It Takes A Village: In the Shadow of David” because while David is the obvious focus of this story, he’s not the only one in it. David is anointed as king to lead God’s people, but not for his own benefit – although he did benefit. David was called to service, a type of service that exists in only a small part of our world. People all over the world recently reflected on the tradition of monarch as servant with Queen Elizabeth II as she celebrated her Diamond Jubilee. David’s service was to and for people the bible rarely mentions, the little people, the insignificant people, people passed over based on birth order or what they look like. Just like David; the irony abounds. So, I invite you to look at and look for all of the people who made David’s reign possible including his royal family because, quite frankly, David isn’t someone who I’d like to model my life and faith on. So I’m going to do a feminist reading of the story this morning. You don’t mind me using the f-word in the pulpit do you? As a feminist, I’m keenly aware of who is in the story and who is missing from this story.

Today we’re going to talk to each other a bit. Who do you think is missing from this story? Think of the sacrifice like a big family celebration. Who is around your table at Thanksgiving?

I’ll give you a moment to answer while I remind you what is going on. Samuel comes to Bethlehem and the elders of the city meet him at the gate, shaking with fear and want to know, “Do you come in peace?” That’s because one verse before our lesson in the previous chapter Samuel kills the Amalekite king, Agag, chopping him into pieces:

1 Samuel 15:32 Then Samuel said, “Bring Agag king of the Amalekites here to me.” And Agag came to him haltingly. Agag said, “Surely this is the bitterness of death.” 33 But Samuel said, “As your sword has made women childless, so your mother shall be childless among women.” And Samuel chopped Agag in pieces before the Holy One in Gilgal. 34 Then Samuel went to Ramah… [Our lesson picks up here]

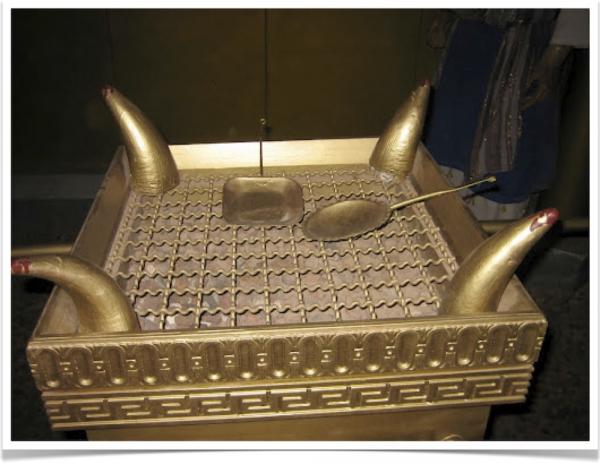

So the elders of Bethlehem were understandably concerned when Samuel showed up. The text doesn’t leave any space between the two stories so for all we know Samuel may have come straight from the execution, having his conversation with God on the road. So Samuel invites the elders to the sacrifice, perhaps to prove the only thing getting killed is the cow.

Back to your quiz: God has sent Samuel to Jesse to anoint the king that God has chosen. Samuel invites all of Jesse’s sons – but we know one, David, is missing – and Samuel invites the elders. Now, who do you think is missing from this story? [David’s mother and sisters, cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents, etc.]

David was only available for God because his parents produced and raised him. We know a bit about his father, Jesse the grandson of Ruth and Boaz. But what about his mother whose name is not preserved? How do I know that David’s mother is alive and that he has sisters?

Later on in 1 Sam 22:3-4, David asks the king of Moab – his great-grandmother Ruth was Moabite – David asks the king: “Please let my father and mother come to you, until I know what God will do for me.” He left them with the king of Moab, and they stayed with him all the time that David was in the stronghold.

So David’s mother was alive. And either Samuel excluded her from the sacrifice only inviting Jesse and the boys or the author of the text ignores her only focusing on Jesse and the boys. Where else would she have been but at her home when the national prophet showed up? Even if she was at market wouldn’t she have gone straight home after that scene at the city gates with the elders? Even if they weren’t invited to the sacrifice, don’t you think everyone in town was as close to the sacrifice as possible? And since sacrifices were done outside there was nothing to keep anyone away – and ancient Israel didn’t practice gender segregation at sacrifices. I think she was there, along with her daughters. Did she at some point offer hospitality to Samuel, a meal and a place to stay and water for his feet? I think so.

David comes from a large family and the names of all of David’s brothers and sisters are given in 1 Chronicles chapter 2. David’s brothers: Eliab firstborn, Abinadab the second, Shimea the third, Nethanel the fourth, Raddai the fifth, Ozem the sixth, David the seventh (1 Chron 2:13-15) and David’s sisters: Zeruiah and Abigail (1 Chron 2:16) They will become the royal family, the village that makes it possible for David to be who he will be and perhaps could be.

Why does it matter who counts and who gets erased? It matters as we try to understand what lessons this story has for us. Many folk read the scriptures through the lenses of the major characters. But we can’t all be David. Who are you in this story? Are you even in this story? Are you David’s parents or sisters? Think about the fact that we know their names unlike the sisters of Jesus from last week. Are you one of David’s brothers, one of his nephews – I’ll tell you about them in a bit – or even one of the many, many, women in his life? (Solomon got that thing honestly, from his father.)

The lessons for us today in this passage of scripture are not literal – we will not be anointed king of Israel or America. Yet this is a scriptural story passed down to us. It may be that God has seen something in us like David, that we are full of promise and possibility. And there is the promise and potential of all the other folk in our village, some of which gets overshadowed by the radiant gifts of a select few. But none of us will be who we are and who we will be, who we can be, on our own. We come from families that shape us for good and for ill, and from communities, neighborhoods, schools and our larger culture. And many if not most of us participate in more than one culture. And we are also responsible for our own choices, including the choice to nurture the dreams and aspirations of other folk in our villages. How will we live up to and into our own possibilities and promise and at the same time, how will we help those around us live up to and into theirs?

David’s family supports him; his successes are largely family affairs. David is supported by three men who have his back at every turn, his nephews, the sons of his sister Zeruiah: Abishai, Joab, and Asahel. Contrary to much of biblical tradition, their father is erased from the text; his name is not preserved and they are known by their mother’s name. David’s nephews are the commanders of his military forces and his personal guard. They hunted down and killed everyone who rebelled against David personally – including David’s son Absalom. David didn’t put himself on that throne and he didn’t keep himself on that throne. And when one of Saul’s men killed one of David’s nephews in battle they hunted him down and killed him after the battle was over.

David’s other sister, Abigail, gave birth to his nephew Amasa, unfortunately he sided with Absalom and was killed by Joab, one of those first three nephews. (1 Chron 2:16-17) Amasa’s father, David’s brother-in-law was Jether the Ishmaelite, so David is related to the children of Ishmael and Israel in addition to being the great-grandson of a Moabite woman. David’s village transcended socially acceptable boundaries. The Gospel of Matthew will take it farther and say that Boaz, David’s great-grandfather is descended from Rahab, the Canaanite prostitute.

David’s complicated family history is a reminder that royal families are not different from our families in most ways. We’ve all got stories and skeletons. The feminist practice of naming those rendered invisible and silent paints the Israelite royal family in a whole new light. David’s family would be right at home in a reality show, but they are nearly lost to the long shadow cast by David in the glare of the light shone on David by the writers of the scriptures, nearly eclipsing everyone else.

And of course, there are all of David’s women: Merab whose engagement to David was broken by her father Saul, Michal whose marriage to David was ended by her father Saul who gave to another man; she was taken back and imprisoned by David, Abigail with whom he apparently never had children. And then there are all of the women with whom he did have children: Ahinoam whom he married on the way home with Abigail after their wedding – ick!, Maacah, Haggith, Abital, Eglah, and Bathsheba.

When I teach the biblical account of David’s rape of Bathsheba I start with the fact that David has at least six wives with whom he is living, sleeping and making babies. They are in addition to his banished wife, Michal. David has also two collections of women described as “other primary and secondary wives taken in Jerusalem” and he inherited “Saul’s former wives.” David has sexual access to as many as a dozen women if not more when he walks out onto that roof sees Bathsheba and gives the order to have her abducted and brought to him so that he can do as he pleases.

There were consequences to all of David’s womanizing which he admits in his lesser-known psalm of repentance, Ps 38:

1 Holy One of Old, do not rebuke me in your anger, or discipline me in your wrath.

2 For your arrows have sunk into me, and your hand has come down on me.

3 There is no soundness in my flesh because of your indignation;

there is no health in my bones because of my sin.

4 For my iniquities have gone over my head; they weigh like a burden too heavy for me.

5 My wounds grow foul and fester because of my foolishness;

6 I am utterly bowed down and prostrate; all day long I go around mourning.

7 For my loins are filled with burning, and there is no soundness in my flesh.

David has apparently contracted a sexually communicated disease. And, lastly, there was Abishag with whom he was impotent before he died – yes that is in the bible. Did God really know that David would do all of these things and choose him anyway?

Saint Augustine famously described God as omnipotent, omniscient and omnipresent. However in the bible, God seems to never be more than two o’s at a time. When God looks on David’s heart, what does God see? Perhaps God did see all of David’s brokenness and knew that it was still possible for David to be the man that God called him to be. And I think that’s good news for the rest of us. Amen.

Leave a Comment