Welcome to Wading in the Waters of the Word™ with A Women’s Lectionary

Gentle Readers, Followers, Preachers, Pray-ers, Thinkers and Visitors, Welcome!

Welcome to this space where you can share your worship – liturgy and preaching – preparations – using A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church. We begin in Advent 2021 with Year W, a single, standalone Lectionary volume that includes readings from all four Gospels. (We will continue with Year A in Advent 2022 to align with the broader Church.) In advance of each week, I will start the conversation and set the space for you all. I will come through time to time, but this is your space. Welcome!

Media Resources

A Women’s Lectionary For The Whole Church

Session 1, October 16, 2021

Rev. Wil Gafney, PhD at Myers Park Baptist Church

Plenary 1 | Translating Women Back Into Scripture for A #WomensLectionary

This session introduces participants to frequently unexamined aspects of biblical translation in commonly available bibles and the intentional choices made in “A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church.”

A Women’s Lectionary For The Whole Church

Session 2, October 16, 2021

Rev. Wil Gafney, PhD at Myers Park Baptist Church

Plenary 2 | Reading Women in Scripture for Preaching, Study, and Devotion

This session provides an overview of “A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church,” its genesis, production, and content. There is also an in-depth exploration of specific passages appointed for specific days including time for public and private reading and discussion.

Lectionary Lectio

Click the Comment links to add to the conversation

Could You Not Stay Woke?

Jesus said, “My soul is deeply grieved, to the point of death; you all stay here, and stay awake… Mark 14:34

Let us pray: Holy One of Old, open our eyes. Amen.

Could you not stay awake one hour?” Mark 14:37

Could you not stay woke?

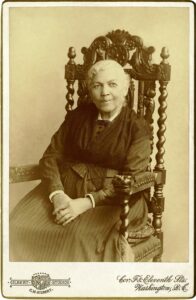

Billie Holiday was designated the most dangerous person in America because she would not stop singing “Strange Fruit.”

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Lady Day, our gardenia scented blues prophet, would not silence her prophetic cry against a white supremacist government that endorsed terror tactics to murder the civil rights movement and our leaders, of which she was one.

The government’s full throated defense of lynching and those who lynched — including pastors and politicians — manifested itself as an FBI initiative to seduce Billie Holiday back into the heroin needle from which she had freed herself, drive her to madness and bankruptcy and, many believe, deprive her of proper and prompt medical attention in her last days to hasten her demise. But the words of a prophet do not die with the prophet. Her words survived.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Billie Holiday, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Fred Hampton, Jr., Malcom X and Angela Davis were each identified as one of if not the most dangerous person in America by that same FBI and they did not all survive the infiltrators and assassins the FBI sent against them. But their words survived.

Each one of them challenged the legitimacy of a white supremacist oligarchy disguised as a western democracy built on the backs of stolen black folk and stolen black labor and stolen black wealth. Each of these persons, prophets, preachers, poets, protesters and professors saw the world as it was beneath the surface where power and wealth and privilege and bias are the only seats at the table that matter. Some might say their third eye was open. They were awake to the realities of this world as if they had taken the red pill and suddenly seen the world without its white washing matrix painting a picture of nothing to see here, Jedi mind trick. They were awake. And call us to wakefulness but we keep slipping and sleeping. Because wakefulness is hard.

Wakefulness is terrifying. To be awake, to be woke, means to see and live nightmares day and night. It means to see the world as it is, #NoFilter. It means to see that we will not soon be done with the trouble of the world, no, not soon enough. It means there’s no rest for the weary. It means that often there is no peace but the peace of death. And so we sleep. But as Fiddy Cent’s character, Kanan Stark, said, “sleep is the cousin of death.” We are sleeping ourselves to death. And the forces of empire that profit off of our lives and our deaths are playing the lullaby. Could you not stay awake one hour? Could you not stay woke?

In the summer of fire, 2014, black men and boys were being shot and strangled and suffocated by police departments across the country in a cascade of violence. As a result many are able to call the names of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. But the police also executed Yvette Smith and Tyree Woodson, Shonda Mikelson and Dawn Cameron, Aura Rosser and Akai Gurley and, Tamir Rice and Victor White and Ariel Levy all in the same year. And when the Black Lives Matter movement erupted into public view, a black cultural folk expression began to be heard beyond the cultural curtain that protects black stuff, black speech and black space. Stay woke. Stay awake. Could you not stay awake one hour?

But folk did not stay awake. If you woke up when Tyre Nichols was chased down and hunted for sport in the street like an animal, you woke up because you were sleeping on police violence against black and brown folk when it wasn’t in the news every day. Could you not stay awake one hour? Could you not stay woke one hour? The people saying the Black Lives Matter movement is “over” want you to go back to sleep. When defund the police was deemed to be too woke, a lot of folk did go back to sleep. Folk were woke when it was cool but silent when the term was co-opted and bastardized and became the newest way to say the N-word. Folk with tattered black lives matter signs in their front yard making cringe woke jokes. Could you not stay awake one hour? Could you not stay woke one hour? I see you slipping and sleeping. And I see you sleepwalking through protests on your way back to bed. And I just came by to tell you stay woke.

You see, there was a mama’s boy from Nazareth and folk slept on him too. [Some folk are still sleeping.] They called him Jesus, Yeshua, Mary’s baby and Joseph’s maybe, calling him fatherless by calling him the son of Mary. But they also called him a healer and a miracle worker. They called him and magician and they called him a sorcerer. They called him lord and master and teacher and rabbi. They called him Messiah, the Christ of God, the King of Israel and the Son of the living God. They called him a threat to the empire and to Caesar’s claim of godhood. They called him a threat to Herod’s throne. They called him Jesus, a mama’s boy from Nazareth.

They called him soft on crime like adultery. They called him a socialist for the redistribution of wealth – fishes and loaves, coats and cloaks. They called him a womanizer with lowbrow taste in even lower women. They called him a glutton and a drunk, and not just guilty by association. They called him a thug who ran with thugs, some of his boys were quick to cut you and have you leaving with fewer parts than you came with, but he could fix that up too. They called him ignorant – six days a week you can heal folk but since you obviously don’t know how sabbath works let me tell you why can’t do any healing up in here on today. They called him the one the devil couldn’t deceive or seduce. They called him out his name while he was calling folk out their graves. They called him everything but a child of God. But they also called him by David’s name; they called him Jesus, the Son of David. I call him the Son of Bathsheba.

There was a mama’s boy from Nazareth who came into town like the son of Bathsheba and not like the son of David. Jesus rolled into town like his mama’s son, like his many times over great grandmother Bathsheba’s boy. He came without a chariot and without a crown. He came without an army and he came without a sword. He came without a record of atrocity and he came without a treasury. He came without a red carpet and he came without a body man. He came without whispers of sexual misconduct. He came on third class transportation. But he came woke.

Jesus came into town with his third eye open to the terror and torture that awaited him. He was awake to sin and suffering. He was awake to love and loss. He was awake to belonging and betrayal. He was awake to faithfulness and faithlessness. He was awake to finite mortality and infinite mystery. Jesus was fully awake and he asked for those who followed him, who loved him, who served him and served with him to stay awake with him. The crowds and applause were gone. It was just them watching a man who was more than a man pray a prayer yielding to a death that terrified them.

Jesus said, “My soul is deeply grieved, to the point of death; you all stay here, and stay awake… Could you not stay awake one hour?”

Could you not stay woke?

Those boys who said they were his ride and die choose not to see his sorrow and struggle. They chose not to bear witness to this terribly intimate moment. They let sleep take them so they wouldn’t have to see the world as it is. They didn’t stay awake. They didn’t stay woke.

But Jesus, Mary’s baby boy with the grandiose claims about a God and father who were one and the same, stayed awake. He stayed awake to wrestle with God while it would’ve been easier to curl up and have a last few minutes of sleep. He stayed awake to betrayal by one of his closest friends. He stayed awake through the helter skelter choreography of an unjust legal system. He stayed awake through police brutality and battery. He stayed awake through his body’s’ pain and his mama’s tears. He stayed awake. He stayed woke. Jesus didn’t close his eyes do the evil that men do not even when they were doing it to him. He didn’t close his eyes to financial or political corruption. He didn’t close his eyes to the atrocities an occupying force commits against a subject population. He didn’t close his eyes or his ears or his heart to the potential for repentance and reconciliation even as he hung up on the cross. And when he did close his eyes in Lady Death’s cousin, Sleep, it would only be for a moment or two or three. But not yet.

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop

Here is a strange and bitter cr—

This week some of us will reenact the long days and nights in which Jesus stayed awake. But that ritual liturgical reenactment has no meaning if we are asleep to the world around us and its needs. Jesus is still calling us to stay awake and stay woke. Stay woke to history or we shall surely repeat it. Stay woke in the midst of seemingly overwhelming odds to fight against anti-trans laws and fight for gun safety laws. Stay woke to brazen fascism in Europe and Canada and right here at home in America with the three K’s. Stay woke to the white supremacist domestic terrorist threat at every level of our society, culture, legal and justice systems. Stay woke to antisemitism and its roots in Christianity and in some of our continuing and current theologies. Stay woke to Christian Zionism and the deployment our tax dollars, military training and equipment to maintain and expand the occupation of Palestine and the apartheid restrictions against Arab Israelis with with second class passports. Resist the urge to curl up in a puddle and go to sleep. But if you do close your eyes, black folks say, “every closed ain’t sleep.” When you close your eyes this week, close them in prayer. Not the empty refrain of “thoughts and prayers.” Pray the prayer of preparation and pray the prayer of participation, but never the pray the prayer of resignation.

Don’t let those who have a vested interest in you sleeping shame you out of staying woke. We’ve already seen what happens when we fail to stay awake and stay woke. Some folks slept on a reality show buffoon with a long history of rape and racism and only woke up when he woke up in the White House. Some folks slept on the security of reproductive health care and only woke up when the cable news told them they were now living in Gilead. Some folks slept secure on access to the right to vote being secure and then woke up to a Supreme Court that said corporations were people and the states that denied access to the right to vote no longer needed monitoring. Some folks slept on judicial appointments and local elections, school boards and library collections. We can’t afford to sleep anymore. We can’t afford it for our children and we can’t afford it for our neighbors. We can’t afford it for this nation and we can’t afford it for the world. Stay awake. Stay woke.

Stay awake and see all the ways God is partnering with us in these nightmares. Don’t sleep on God. Don’t sleep on those through whom God works. Don’t sleep on disability activists. Don’t sleep on angry, sick and tired black women. Don’t sleep on LGBTQIA folks who are never going back into those closets unless it’s to pull out something fabulous for their next drag show. Don’t sleep on children and teens creating the movements that will reform gun culture in America and move the needle on human made ecological carelessness and catastrophe. Don’t sleep on the mama bears of trans children. And if you are awake, why don’t you join us. There’s a long day’s work ahead and miles to go before we sleep.

Could you not stay awake one hour?

Could you not stay woke one hour?

Palm Sunday 2023

Gonna Take A Miracle

Epiphany V: 2 Kings 5:1–4, 9–14; Psalm 30; Acts 16:16–24; Matthew 9:18–26

Year A, A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church

God of miracles, hear your people’s cry. Amen.

Harriet needed a miracle. There was a woman named Harriett Jacobs who liberated herself from enslavement – not Harriett Tubman, another woman. And as she was being tracked through the woods, she prayed a very specific prayer, to Daniel’s God, who got him out of the lion’s den. She needed a miracle, and she turned to the God of miracles. She received her miracle. But not everyone who prays for a miracle receives divine intervention and heavenly help.

On 7 January, a young father and amateur photographer was chased to his death through the streets of Memphis Tennessee. He did not get a miracle. Tyre Nichols was brutalized, tortured, and ultimately, murdered by the social, cultural and political descendants of the slave catchers who chased Harriet through the woods, intent on stealing her freedom or her life.

Tyre Nichols and countless others sit with us as we read the miraculous stories in our scriptures calling us to account, requiring us to articulate a theology that does not make mockery of their suffering and death as we try to make meaning of the miraculous stories that are our scriptural heritage. Because, if it is not good news – salvation and liberation – for the least of these, for those on the margins of the texts and on the margins of of society in our world, then, it’s not good news. Epiphany is the breaking through of God into the world for all, not just for some.

In the scriptures, God reveals Godself in supernatural occurrences. In most of the gospels, miraculous healings are the primary way Jesus demonstrated that he was not just talking smack. In Matthew and Luke, Jesus comes into the world miraculously; he comes into his own bestowing miracles of healing and resurrection, wherever he goes. There are even some stories that some of his disciples were able to do the same after his death and resurrection and ascension. Paul certainly has the power in our second lesson. But he also is blinded by his privilege and cannot see the enslaved girl in that text as anything but an annoyance.

Let us never overlook or excuse enslavement in the Scriptures or in the ancient world. “That’s just the way it was” is not good enough. Harriet Jacob tells us in her autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Celia, no last name, in her memoir Celia, A Slave, along with scores of other women and men who survived American chattel slavery — and some who did not — they left us their testimony telling us that they always knew they should be free. That’s why there were so many slave revolts and attempted rebellion. That’s why there were so many slaves catchers policing the enslaved.

The ones who have the authority to speak on the terror of enslavement and life as a marginally free person are not those who profit from it, still, or whose worldview is dependent upon it. Human trafficking in any era is an atrocity. And we should be disturbed that the same Israelites who prayed for their liberation in Egypt went into Canaan and enslaved other mothers’ children.

My ancestors prayed for a miracle and we received our freedom. And we are still praying, because we are not yet all free. Yet I still believe in miracles. And I invite you to do so too. Suspend your disbelief when reading the scriptures, just as you do at the movies or when reading a novel. Believe that you are in a galaxy far far away, believe that there is one ring to rule them all, believe that resistance is not futile. Because, in the literary world of the gospels, miracles are more than literary devices. Miracles are ruptures in reality where God breaks through, and does the impossible in human view. We see it in every lesson of our scriptures today. But we don’t always see miracles in our lives, in our world, in our time of need.

Last week we were called to remember Makna Kamiano, Father Damien, and the work he did at Kalaupapa where he lived with, loved, and cared for thousands of people who were ostracized, isolated, rounded up and, all but abandoned because they had leprosy. In older translations of our first lesson, the skin disease that afflicts the Aramean or Syrian, general is translated as leprosy. While it’s important to note for the record, that this ancient skin disease is not Hanson’s disease, the disease, to which Makna Kamiano also succumbed – there was no loss of fingers or facial features in the biblical disease – it was still a devastating diagnosis leading to ostracization and public humiliation.

And then, there was a miracle for this enemy of Israel, a man who killed and enslaved her people. One thing all of these miracle stories teach today is that those with power in the world have no power over the world. The general held power over his troops, power over his household, power over the women, men, girls and boys he enslaved, but he had no power over his own diseased flesh. The miracle came about because a girl who was enslaved in his household testified to the miraculous power of her God and the prophet of her God. In fact, this enslaver, this colonizer, almost missed out on his miracle because he went straight to the source of power as he understood it, the king and not the prophet. He couldn’t receive his miracle because his privilege blinded him. And when the prophet did not perform to his expectations he almost missed out again. He was looking for pomp and circumstance, and maybe a liturgy like the Episcopal Church, smells and bells, incense and chimes. Definitely not go jump in some foreign river. But eventually, he humbled himself and set his power and privilege aside for a moment and, he got his miracle. A happy ending. But is it? As I read and tell this story, I ask where was baby girl’s miracle? And what is her name? Where was her mama? I wonder if Saint Kamiano read this story to his community and if they asked, “Where is our miracle? Where is our healing?” Would he reply like me, “I still believe in miracles. But sometimes it’s hard to believe.”?

In our world, talk of miracles can be dangerous; they are food for starving people. The folk talking the most about miracles are often frauds, seeking to defraud those most desperately in need of a healing or saving touch. Real miracles are unpredictable. They are not dependent on us. And yet, Jesus tells the woman with the vaginal hemorrhage that her faith has saved her.

This unnamed woman’s faith in the possibility that the stories about Mary’s baby boy just might be true motivated her to subject herself to public humiliation, to crawl through a crowd to touch Jesus. Her infirmity, bleeding through a part of her body a whole lot of preachers have refused to name for 2000 years, left her as isolated and ostracized as any leper in ancient Israel or Kalaupapa. She probably had a somewhat clear path to Jesus because people would’ve been jumping out of her way. Her faith moved her to ask, to trust and, that is what put her in the position where Jesus, who did not shrink back from her touch, was able to proclaim that her miracle happened while she was doing the work to pursue her own healing. Beloved, Jesus was not saying that if you just pray hard enough or believe deeply enough, you will get your miracle. Don’t let anyone shame or blame you for not being able to praying away or believing away death and illness.

Miracles are rare in our world but they are all over the place in the scriptures, in our readings for today. Some people try to explain away miracles by saying things like, “the Red Sea was really low, when the Israelites crossed,” or, “everyone brought their lunch, that’s how a multitude was fed on two fish, and five loaves of bread.” I urge you to resist that practice, and let the miracles be miracles, inexplicable. And as we accept the extraordinary ways in which God showed up in the lives of her people in our sacred stories, let us ask where is it, that God shows up in our world, and in our lives. Because we need a miracle in this country. More than one.

The first lesson calls us to listen to those who have only been deemed fit for enslavement, captivity and incarceration. Because in desperate circumstances with no miracle on the horizon, there is where the stories of God are kept alive. There is where we learn something about faith, where we encounter a belief in God that does not waiver even though she may have never lived to see a day of freedom. That is the story of ancient Israel, people who went from being enslaved to enslaving to subjugation to captivity to exile to occupation. That is why the gospels are occupation literature. They are activist writings. They are movement manifestoes. The scriptures that we share with our Jewish kinfolk are scriptures of resistance. They are slave narratives. Like those of Harriet Jacobs and Celia who was put to death in Indiana for resisting the enslaver who violated her body. Her case went up to the state Supreme Court where her conviction was upheld on the grounds that she had no right to defend herself because she was a slave. She needed a miracle and didn’t get one.

Where was God for her when she needed a miracle? Where was God for Tyre when he needed a miracle? Where was God when my people endured 460 years of chattel slavery? Where was God when the Israelites were enslaved for 400 years? Where is God when black folk are afraid to send their sons and daughters out of the house? Where was God when Brianna Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson and, Botham John were all shot by police in their own houses while they were minding their own business? Where was God seven year old Ayana Stanley-Jones was shot by a police officer while she was sleeping on her grandmother’s couch? They didn’t even have the chance to be terrorized at a traffic stop. Where is God? Where is God when Israel is occupying Palestine and some Palestinians are fighting back in horrific ways? Where is God? Where is their miracle?

Miracles meet us between our deepest need and most desperate hope but, a miracle is not a plan. Waiting on a miracle to change the world isn’t going well. When that hope is kindled into faith, not just belief, but a living faith, we discover that our cries do not fall on deaf ears and that we are never alone in our sorrow, grief or illness. We discover desperate circumstances need not leave us hopeless. We discover that there is something miraculous in us that enables us to survive the unthinkable. We discover that there is power in us to transform the world. And we start by making sure everyone has the same chance for life and liberty.How we change our world and break out of some of the cycles that imprison and enslave us is to see our salvation bound up with the liberation of each other. It is to stop making excuses for terror in our Scriptures and terror on in our streets. It requires us to stop reading with whoever we think is the hero and look for the characters on the margins in the text and in our streets and, learn to read and hear some of the characters you’ve overlooked and the ones the text leaves on margins and sometimes, on the cutting room floor. Someone said, “You can’t change what you don’t acknowledge.” We can’t acknowledge what we refuse to see and, when we reject what is hard to hear.

God told Moses that her people’s cry had not fallen on deaf ears. My ancestors clung to that promise. They put their faith in the God of Moses in the same way Harriett Jacobs put her faith in the God who saved Daniel from the lion’s den. The keeper of the flame of faith is most often those on the bottom and those on the margins, the ones most in need of a miracle. When the odds are ever in your favor, faith is a luxury.

Where are our miracles today? They are in the hands of those who do the work to make the miraculous possible. The end of chattel slavery in this country wasn’t a miracle from heaven. It was the work of women and men who walked away from terror and ran away from slaughter and, women and men who worked for the abolition of enslavement in this country and around the world. And some are still working at it for, slavery exists in lots of forms, including some still among us. A treatment and, in some cases, a cure for Hanson’s disease, leprosy, did not come in a miracle from heaven. It came because people did hard work including putting themselves at great risk for others.

I still believe in miracles. I still believe in divine intervention. But I know that what will heal us as a nation will not fall from heaven. It was faith and feet that allowed Harriet to run away from wolves in the human skin. It was faith and love that allowed Damien to lie down with lepers. It is faith in a justice that transcends the brokenness of our systems that keeps black folk in the courts and in the streets. It was faith in the consciences of white people that sent civil rights protesters into spaces where they knew they would be beaten and bitten and pummeled with torrents from fire hoses. It was faith in the decency of the American public that led Mamie Till Mobley to let Jet magazine photograph the murdered remains of her son in an open coffin to try to being an end to lynching. It was that same faith that led RowVaughn Wells to say release the video and show them what they did to my baby Tyre. It is faith that sustains us when there is no miracle. And some days I have faith too. Some days I believe in miracles.

But when faith fails and miracles are scarce I still believe in Mary’s miraculous baby. I believe that God’s precious child who was beaten bloody by the police before he was murdered by the state and cried out to his mama before he died, will reward our faith and faithfulness and, our faithlessness and, all that is broken will be made whole. But we don’t have to wait for that miraculous day. We can bring healing and hope into the world through a faith that compels us to speak and act out of love and hope. I believe in miracles. Amen.

All Saints Kapa’a